On October 23, 2001, less than two months after the 9/11 terrorist attack, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services issued the proposed Model State Emergency Health Powers Act (MEHPA). The proposal was finalized in December 2001. It authorized state health officials and their designees to take control of people, property, health care, communications and more in a public health emergency. State legislatures debated it in 2002. Nearly 40 introduced it and 20 states passed some version of it. Most of the public is not aware of these police powers.

Texas MEHPA In the News on Ebola

Texas Health and Safety Code, Chapter 81, Communicable Diseases (Subchapter E. Control)

State Emergency Health Powers

The Centers for Law and the Public’s Health: The Model State Emergency Health Powers Act

The Model State Emergency Health Powers Act – October 23, 2001 draft

The Model State Emergency Health Powers Act – December 21, 2001 final

BROAD POWERS:

RWJF provides “Turning Point” funds to expand public health powers. In South Carolina, Health Department officials worried about losing power and instead, they “felt their laws were sufficiently general to cover any unforeseen circumstance.” (p. 6)

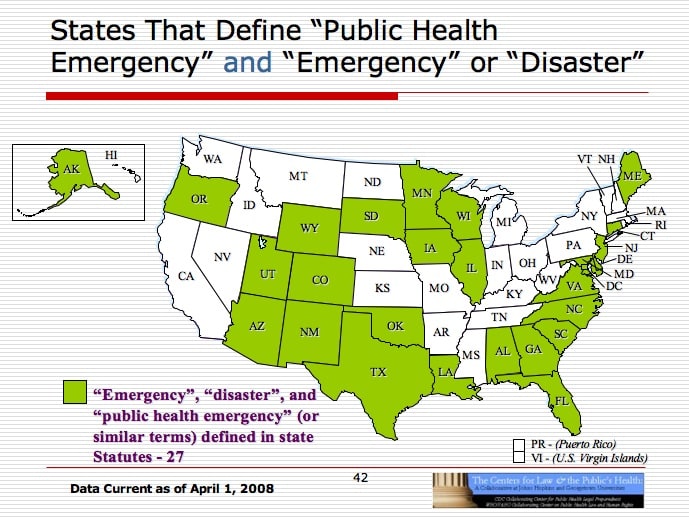

State by State – Government Health Powers Laws

Broad Opposition

Model State Emergency Health Powers Act – American Civil Liberties Union

Although extraordinary measures may be required during an emergency, the Model Act is replete with civil liberties problems. Its three top flaws are that:

- It fails to include basic checks and balances. The Act would grant extraordinary emergency powers, but that kind of authority should never go unchecked. Public health authorities make mistakes, and politicians abuse their powers; there is a history of discriminatory use of the quarantine power against particular groups of people based on race and national origin, for example. The lack of checks and balances could have serious consequences for individuals’ freedom, privacy, and equality. The Act lets a governor declare a state of emergency unilaterally and without judicial oversight, fails to provide modern due process procedures for quarantine and other emergency powers, it lacks adequate compensation for seizure of assets, and contains no checks on the power to order forced treatment and vaccination.

- It goes well beyond bioterrorism. The act includes an overbroad definition of “public health emergency” that sweeps in HIV, AIDS, and other diseases that clearly do not justify quarantine, forced treatment, or any of the other broad emergency authorities that would be granted under the Act.

- It lacks privacy protections. The Act requires the disclosure of massive amounts of personally identifiable health information to public health authorities, without requiring basic privacy protections and fair information practices that could easily be added to the bill without detracting from its effectiveness in quelling an outbreak. And the Model Act would undercut existing protections for sensitive medical information. That not only threatens to violate individuals’ medical privacy but undermines public trust in government activities.

The act is a throwback to a time before the legal system recognized basic protections for fairness; before public health strategies were rooted in voluntary compliance; and before the information age dictated the need for privacy protections of individuals’ personal information.

“State Legislators’ Council Holds Forum on Model State Emergency Health Powers Act,” Institute for Health Freedom on panel hosted by the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), March 1, 2002

The conservative constitutional scholar John Armor strongly opposed the MSEHPA and recommended that state legislators pass resolutions asking Congress to explain why federal funds are being spent to draft the model state legislation. (The CDC awarded Professor Lawrence Gostin $300,000 per year for up to three years to develop the model legislation, among other projects.)

Sue Blevins stressed that the MSEHPA is moving quickly in various states and that lawmakers should pay close attention to definitions included in the proposed legislation. She also cautioned state legislators to beware of those who are using the September 11 attacks as an opportunity to push through their pre-attack agendas.

Jonathan Turley, a well-known liberal constitutional scholar, warned the ALEC members that at perilous times government can do things that are harmful “because government power operates a lot like a gas in a closed space.” He explained “that as you expand the space, the gas fills it completely and absolutely. And it is hard often to restrict that gas again…In times of crisis is when that space expands and it often expands with very little foresight and very little consideration.”

Minnesota State Emergency Management and

Government Health Powers Statutes

Minnesota Statute 12.21

Minnesota Statute 12.28

Minnesota Statute 12.31

Minnesota Statute 12.32

Minnesota Statute 12.34

Minnesota Statute 12.39

Minnesota Statute 12.61

Minnesota Statute 144.419

Minnesota Statute 144.4195

Minnesota Statute 144.4196

Minnesota Statute 144.4197

Minnesota Statute 148.235

Minnesota Statute 151.37

April is “Truth About HIPAA” Month!