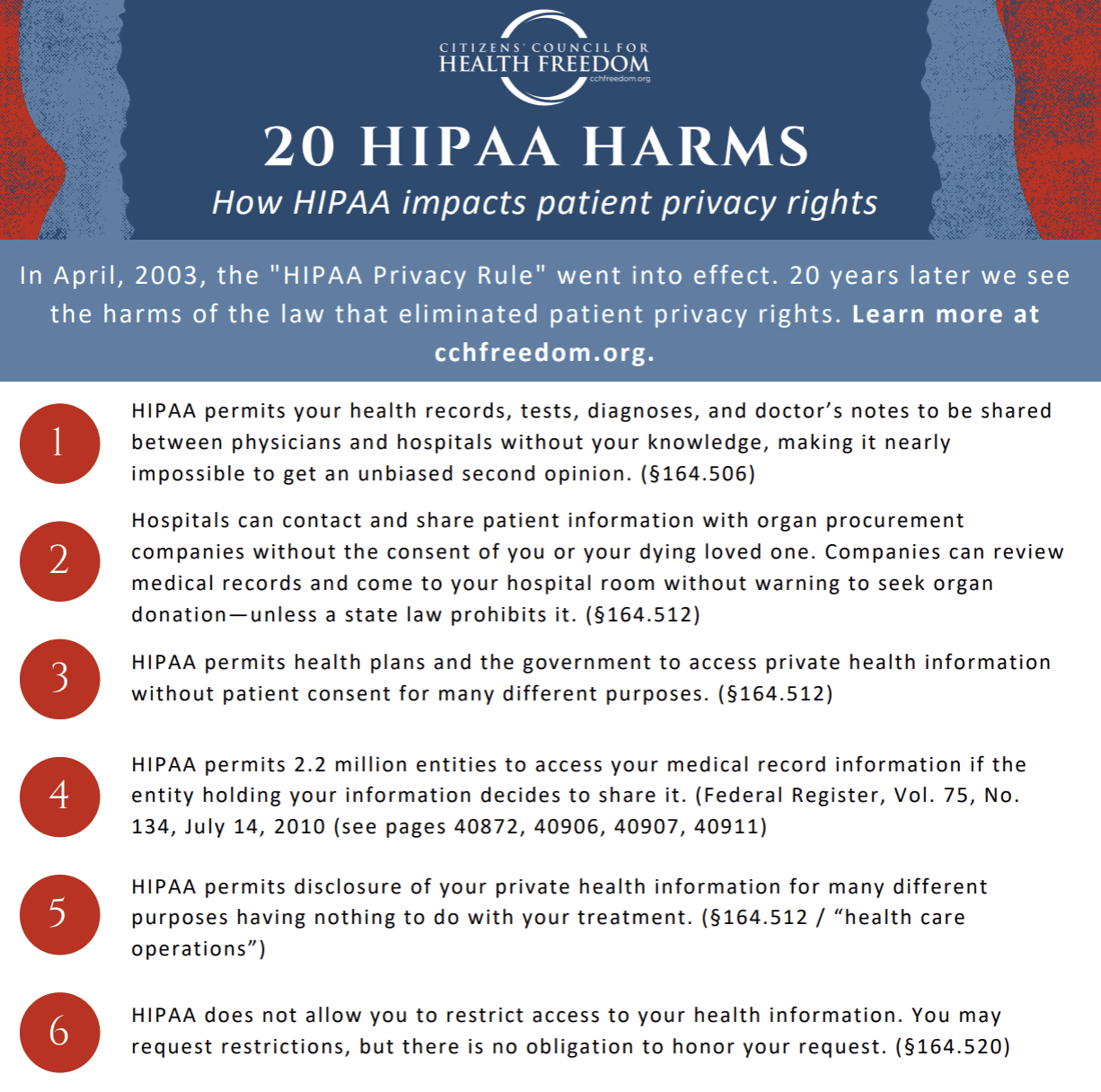

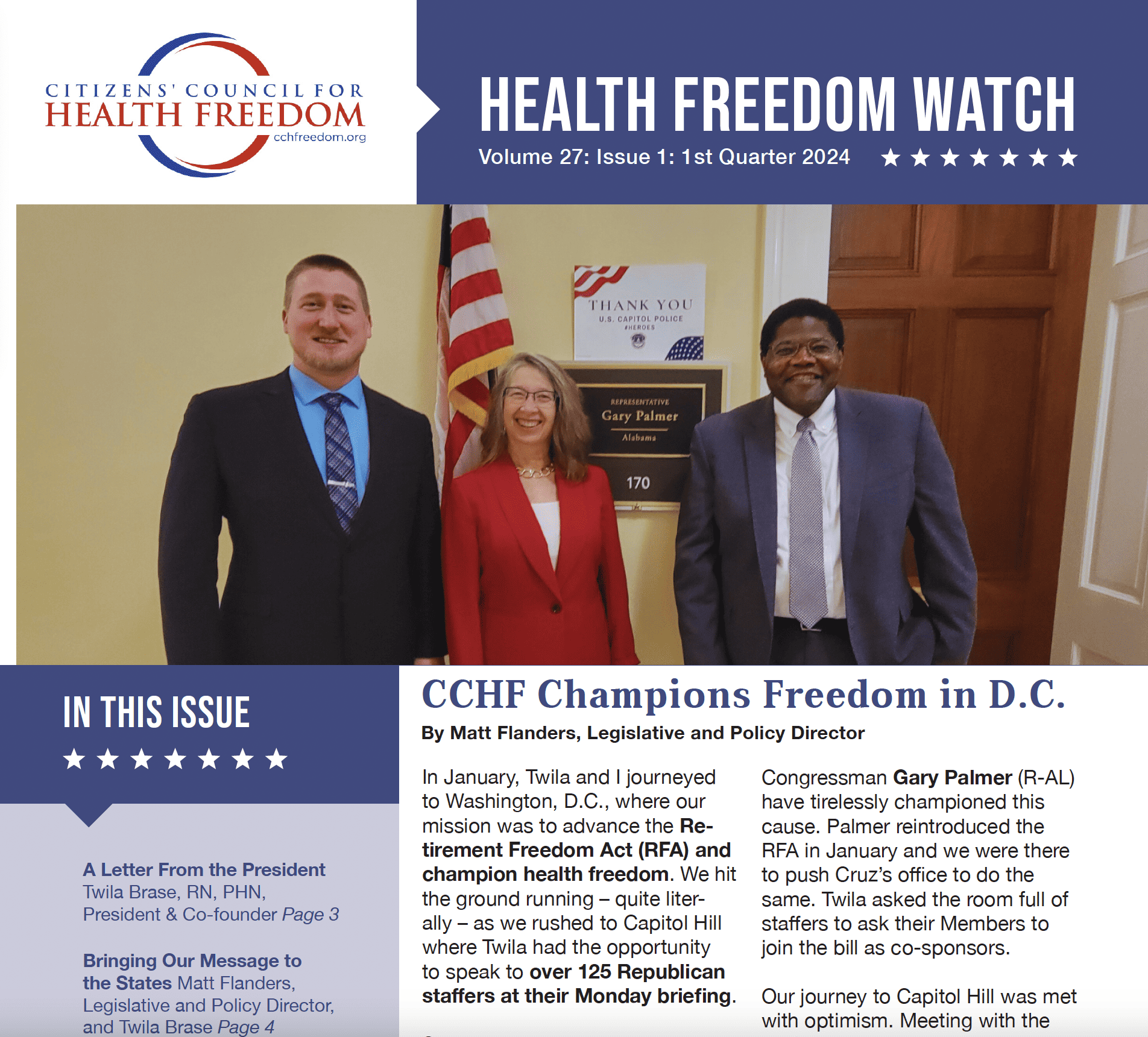

Publications

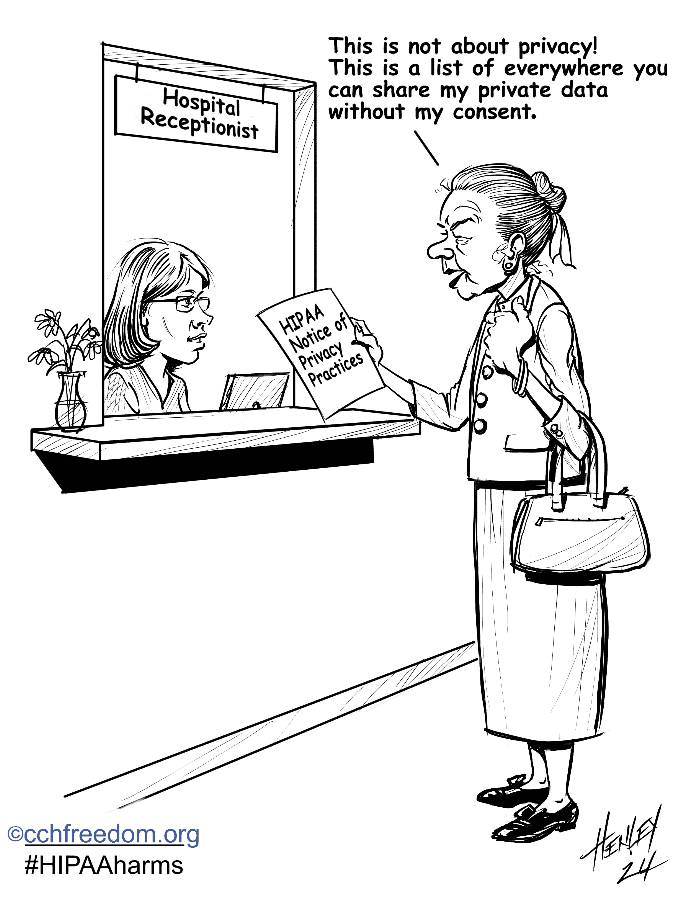

When it comes to fighting for health freedom, information is key and knowledge is power. You can find CCHF’s latest content – as well as our archived content – here on our website. From original papers and articles to issues of our quarterly Health Freedom Watch, this is where we add published content to keep you informed.

Key Initiatives

Subscribe to the Newsletter

Enter your email to begin receiving monthly newsletter emails.

Visited 4,006 times, 342 visit(s) today